Friday, June 22, 2007

bookworm nightmare: episode one

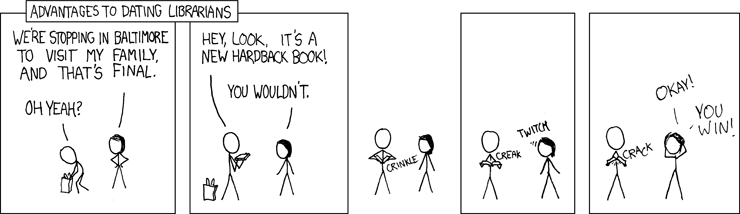

xkcd once again strikes me at my core.

Monday, June 18, 2007

summer reading

So, graduation has come and gone, and I'm nestled once again in central Ohio. Now I'm exploring. I just started preparing for the GRE and have been pulling some things for reading this summer. I need to be ready for the jeopardy game that is the Literature in English GRE...but also I want to read for fun again. It's refreshing really...Since I'm plucking my way through the Columbus Metropolitan Library system, I'll share some of my favorite findings (Lucky you'uns)

My pick today is from 95 poems, E.E Cummings, published in 1958:

8

dominic has

a doll wired

to the radiator of his

ZOOM DOOM

icecoalwood truck a

wistful little

clown

whom somebody buried

upsidedown in an ashbarrel so

of course dominic

took him

home

& mrs dominic washed his sweet

dirty

face & mended

his bright torn trousers (quite

as if he were really her &

she

but)&so

that

's how dominic has a doll

& every now & then my

wonderful

friend dominic depaola

gives me a most tremendous hug

knowing

i feel

that

we & worlds

are

less alive

than dolls &

dream

Thursday, June 7, 2007

final final

Pulling From the Root: Hair Imagery in Sarah Phillips

In his essay Shame and Glory: A Sociology of Hair, Anthony Synnott argues “hair is perhaps our most powerful symbol of individual and group identity…” (381) Hair images in biblical verse, significant works of literature such as Milton’s Paradise Lost, and fairy tales like Rapunzel have helped to shape hair’s symbolic nature in Western ideology. The ability to alter length, color, texture, and style predispose hair to the task of expressing one’s individualism and connection with a community. Because hair is easily manipulated and exists both attached to and an exposed article of a person, it has the unique ability to become an expression of personal or community leanings. A progression of hairstyle as both a political and individual statement is visible in the social history of the Black community in

Andrea Lee’s novel Sarah Phillips works to illustrate both the significance of hair as a factor individual and community identification. As hair serves to connect communities, it equally and oppositely serves to separate communities, as Synnott explains with his “theory of opposites” in which: “opposite sexes must have opposite hair” and “opposite ideologies have opposite hair.” (382) Additionally, as a work of literature by a Black female author, about the personal growth and development of a Black woman in America at the rise of Black feminism, it serves also as an indication of the rise of a separate Black feminism. In their book, Hair Story: Untangling the Roots of Black Hair in America, Ayana D. Byrd and Lori L. Tharps reference “popular beauty guide A Complete Course in Hair Straightening and Beauty Culture”, published in 1919 which makes the claim: “the dressing of one’s hair should be a matter of deep concern…To no other race is this more important than the Negro woman.” (29) Lee’s title character, Sarah Phillips, is conscious of her own hair as well as the hair of those around her. This consciousness that Lee creates emphasizes the importance of hair as a symbol in the Black community as a whole, but also serves to separate Sarah as a Black woman from dominate white culture, as well as the masculine emphasized Black Power movement. Hair as a motif becomes a common denominator that runs consistently throughout Sarah Phillips allowing for comparison and interpretation of the characters surrounding Sarah, as well as Sarah herself.

Sarah’s hair does not conform to the qualities valued in hair by the dominant White culture, and this fact causes her conflict with her friends. While in

The difference between the “Shetland-clad blond” (56) Sarah secretly wishes to resemble, to the perception of her identity by her friends causes her mental turmoil and she attempts to calm herself after the attack: “…still bent double, I turned my head and gently bit myself on the knee. Then I stood up, brushed my hair, and left the bathroom, moving with caution.” (12) Her reaction to their comments on her hair affects her emotionally, and she tries to smooth her hair. By smoothing her hair with a comb, she is attempting to make her hair more closely resemble the hair accepted within dominant white culture. Sarah’s comb which she uses in an attempt to regain her composure, and thus strength in her identity, is the same which Roger commandeers. Roger, who Sarah describes as having “flat brown hair” (6), uses her comb, “stroking his hair still flatter.” (9) The juxtaposition of the images of Roger and Sarah using the comb to flatten their hair is a representation of the power commanded by their physical identity—their hair. Roger’s already “flat” hair is representative of his powerful identity and using her comb to further “flatten” his hair is unnecessary beyond personal gratification and exaggerating his position over her. Her comb is an object which she reaches to in a search of solace, obviously an important possession and in following the symbolic nature of hair, it is a tool which shapes her personal identity. By running the comb through his own hair, he desecrated her attempt at creating an identity for herself within the masculine, white community. Roger violates not only Sarah’s property, but essentially her body itself through proxy. Sarah has no way to reclaim her body in this situation—her struggle to find her identity within a community where she does not completely identify, one where she is surrounded by white men, shows the need for Sarah to have her identity confirmed to her through other means.

There is a great variety in women’s hair, both Black and White, throughout the novel. Sarah’s interactions with other females are highly symbolized through the differences or similarities in their hair. It is through her perceptions of White female characters and her perceptions of Black female characters which make Sarah’s journey toward identifying herself in the female community visible. Ingrid Banks asserts, in her book Hair Matters: Beauty, Power, and Black Women’s Consciousness, “hair becomes a marker of difference that Black women recognize at an early age.” (23) The discrepancies in her identification with women in dominant White culture are manifested through her visions of their hair. At her father’s church Sarah observes the small group of white students who came to see her father speak and she notices that “the young women wore their hair long and straight.” (21) Her observation is understated and she does not seem to pass judgment based on that alone, but she does take into account the opinions of the women around her: “…church members whispered angrily that the young women didn’t wear hats.” Synnott explains the tradition of veiling in Christian practice is traced to Corinthians, in which women are expected to exercise “‘taking the veil’, i.e. hiding the hair” (403) in order to eliminate its presence as a symbol of pride or sexuality. Inside the “

Sarah’s own interactions with hair in the church setting not only creates room for comparison between her and the female students, but also her differences between then Sarah and the Black women of her community. Sarah is unsettled within the traditions as she “idly began to snap the elastic band that held [her] red straw hat in place.” She is bound under a hat with braids which creates a distance between herself and Christ; her rejection through the ‘snapping’ of the band, she is essentially questioning the traditions of the church. Sarah made note of the “hollow eyed blond Christ” (17) In Synnott’s theory of opposites, he notes: “blonde and dark hair are polarized as socially opposite, fun and power, and they evoke startlingly different aesthetic and stereotypical reactions.” (388) Her childhood wishes for being blonde which would have allowed her to become part of the homogenized, dominant white culture’s standard of beauty—reappears as an image atop the crucifix. The antithesis of her own identity displayed through her hair is placed as the emblem of faith, representing the church itself. This image serves to demonstrate the void between Sarah and the church—she is unable to also identify with her family and community’s faith. Sarah watched the other children go through baptism but Sarah resists her Aunt Lily’s insistence that she be baptized. When Sarah resists baptism, her Aunt Lily “tug[s] gently on one of [Sarah’s] braids” (20), as if to remind her of her identity as a Black female, symbolized by her hair. Aunt Lily is literally pulling on her hair, pulling her back to tradition—which she refuses.

Sarah is unable to exist fully in a Roger and Henri’s community and she is alienated by the traditions of her father’s church. Disengaged from both the Black and White masculine cultures, Sarah observes the lives and identities of women in her life through their hair. Sarah’s observation of Curry’s girlfriend Phillipa, “a blonde from

There is unity created with the juxtaposition of these images of women, both Black and White, old and young, having overcome complications with their identity and voice. Despite the racial division, the women who are able to move their hair aside are connected by the common experience as women. They struggle, and succeed as being seen as persons, with faces, identity beyond their hair, seeking instead the ability to possess themselves in a way that cannot be violated so simply, so easily, by men. The women who push their hair away from their faces are described in terms which make them appear somewhat haphazard, wild, and free—it is this type of a woman who helped to usher in the second waves of feminism. In a personal introduction to her essay, A Hair Piece: Perspectives on the Intersection of Race and Gender, Paulette M. Caldwell meditates on a comparison of her perspective of her own hair versus that of her grandmother:

“When will I cherish my hair again, the way my grandmother cherished it, when fascinated by its beauty, with hands carrying centuries old secrets of adornment and craftswomanship, she plaited it, twisted it, cornrowed it, finger-curled it, olive-oiled it, on the growing moon cut and shaped it, and wove it like fine strands of gold inlaid with semiprecious stones, coral and ivory, telling with my hair a lost-found story of the people she carried inside her heart?” (365)

Work Cited

Banks, Ingrid. “Why Hair Matters: Getting to the Roots.” Hair Matters: Beauty, Power, and Black Women’s Consciousness.

Byrd, Ayana D. and Lori L. Tharps. Hair Story:Untangling the Roots of Black Hair in

Caldwell, Paulette M. “A Hair Piece: Perspectives on the Intersection of Race and Gender.” Duke Law Journal. 1991.2 (1991): 365-396.

Jacobs-Huey, Lanita. “Gender, Authenticity, and Hair in African American Stand-up Comedy.” From the Kitchen to the Parlor: Language and Becoming in African American Women’s hair Care.

Lee, Andrea. Sarah Phillips.

Synnott, Anthony. “Shame and Glory: A Sociology of Hair.” The British Journal of Sociology 38.3 (1987): 381-413.

Weitz, Rose. “Women and Their Hair: Seeking Power through Resistance and Accommodation.” Gender and Society 15.5 (2001):667-686.

technical error

I haven't been able to post a blog in quite some time--blogger decided that it likes me screen name/password combination tonight. So...horray.Tuesday was my work-day of my undergrad experience. Graduation is day after tomorrow...a little mindblowing. Sometimes it doesn't feel like it's been three years since I was dropped off down here in the hills--sometimes it does. It's had it's interesting (and not so interesting) times, lots of work and procrastination, oh and fun, I had some of that too. It's easy to get disenchanted and wonder if I had the "college experience". Did I join the right clubs? Did I meet enough people? Have I learned something? Am I better person? Did I take full advantage of this time in my life where I have so much freedom and minimal responsibility?

In reflection of my time here I want to share some of the experiences that I have had in my three years:

-Taking a chance and meeting JJ, one of the best friends I've ever had.

-Getting paired with a random roommate, Lana, who turned out to be a great friend and partner in silly crime, and my roommate for the entire three years here.

-Truely, absolutely, hardcore failed biology.

-Declared my major as English--direct result of failing biology. Never looked back.

-Met friends who I plan to keep in contact with, and fully enjoyed the company of people I won't ever see again.

-Decided to learn German.

-Studied abroad (took my first transatlantic flight [alone], lived in a different country, traveled on trains, discovered my love for photography, and collected so many memories I could never rehash them all...retelling cannot do that experience justice)

-Took a quarter with 4 literature course (400+ pages of readying per night, became a hermit, nearly went crazy, and it was one of the most fulfilling, engaging 3 months of my life)

-Gained confidence in myself as a person and my ability to DO something (cliche as it may sound, I've changed a lot in these three years. It really was a chance to reinvent myself. But maybe "reinvent" in the wrong word because, I didn't change myself...I just let myself be. I'm not the shy, self-conscious girl trying to hide in the background. I'm happy in the background or the foreground...as long as it's me.)

Now, I'm fairly positive that this will not interest 99% of my readers enough to read this all the way through--but--this was my final paper that I turned in. It's my blog and I'll bore if I want too.

[edit: essay to be added]